GREAT AVIATION QUOTES

Charles Lindbergh

I hope you find what you are looking for. And maybe discover something you had no idea about!

There are 34 quotes matching Charles Lindbergh in the collection:

He did it alone. We had a cast of a million.

Attributed to Neil Armstrong

Regards Charles Lindbergh.

See six other Neil Armstrong great aviation quotes.

I owned the world that hour as I rode over it — free of the earth, free of the mountains, free of the clouds, but how inseparably I was bound to them.

Charles Lindbergh

On flying above the Rocky Mountains. Quoted in the 1976 book Lindbergh: A Biography.

This is earth again, the earth where I’ve lived and now will live once more. Here are human beings … I’ve been to eternity and back. I know how the dead would feel to live again.

Charles Lindbergh

On sighting Ireland after first solo Atlantic crossing, 1927. In The Spirit of St. Louis, 1953.

This fellow [Charles Lindbergh] will never make it. He's doomed.

Harry Guggenheim

After studying The Spirit of St. Louis at Curtiss Field, 1927.

CAN BUILD PLANE SIMILAR M ONE BUT LARGER WINGS CAPABLE OF MAKING FLIGHT COST ABOUT SIX THOUSAND WITH MOTOR AND INSTRUMENTS DELIVERY ABOUT THREE MONTHS

Donald Hall

Chief engineer, Ryan Airlines, next day reply to Charles Lindbergh’s request for feasibility of the airplane later known as The Spirit of St. Louis. M refers to their Model M. Westerrn Union telegram from San Diego, California, 4 February 1927.

What kind of man would live where there is no danger? I don’t believe in taking foolish chances. But nothing can be accomplished by not taking a chance at all.

Charles Lindbergh

At a news conference after his trans-Atlantic flight, May 1927. Quoted in 2002 book Lindbergh: Flight’s Enigmatic Hero.

Defeat and death stared him in the face and he gazed at it unafraid, intent only on the task he had set himself.

Russell Owen

Rather breathless front page story in The New York Times, describing the departure of Charles Lindbergh from New York, 21 May 1927. At time of publication he was last “sighted passing St. John’s, N.F.” and the success of what became the first solo flight across the North Atlantic was unknown. The two-page dispatch started:

“A sluggish, gray monoplane lurched its way down Roosevelt Field yesterday morning, slowly gathering momentum. Inside sat a tall youngster, eyes glued to an instrument board or darting ahead for swift glances at the runway, his face drawn with the intensity of his purpose.

Death lay but a few seconds ahead of him if his skill failed or his courage faltered. For moments, as the heavy plane rose from the ground, dropped down, staggered again into the air and fell, he gambled for his life against a hazard which had already killed four men.”

Are there any mechanics here?

Charles Lindbergh

First words upon arrival in Paris after first solo transatlantic flight, 10:22 local time 21 May 1927. Quoted in the 1993 biography of Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh, Loss of Eden.

Newspapers at the time posted now discredited accounts with his first words being things like “Is this Paris?” and “I'm ”. Lindbergh’s second sentence was the usual query of the American tourist, “Does anyone here speak English?”

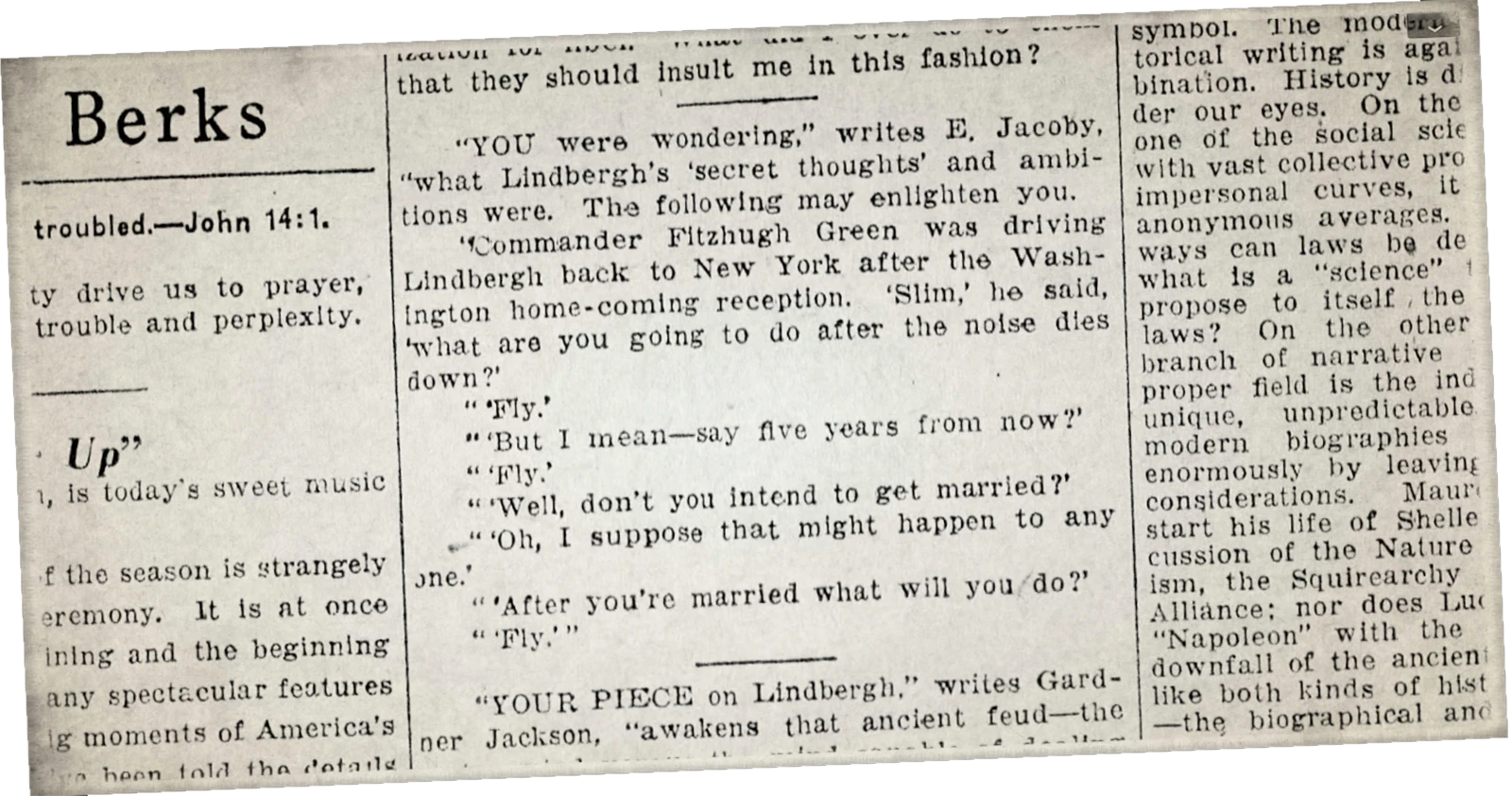

Commander Fitzhugh Green was driving Lindbergh back to New York after the Washington home-coming reception. 'Slim,' he said, 'what are you going to do after the noise dies down?'

'Fly.'

'But I mean—say five years from now?'

'Fly.'

'Well, don't you intend to get married?'

'Oh, I suppose that might happen to anyone.'

'After you're married what will you do?'

'Fly.'

Charles Lindbergh and his chief secretarial aide Fitzhugh Green

Story in several 1928 publications, including The New York World newspaper and U.S. Air Services magazine. This copy from the Reading Times newspaper, Reading, Pennsylvania, 18 April 1928. While probably planted by Green, it rings true to Lindy's concise speaking style and his deep love of flying.

My father had been opposed to my flying from the first and had never flown himself. However, he had agreed to go up with me at the first opportunity, and one afternoon he climbed into the cockpit and we flew over the Redwood Falls together. From that day on I never heard a word against my flying and he never missed a chance to ride in the plane.

Charles Lindbergh

We, 1928.

After reading … accounts … of minor accidents of light, it is little wonder that the average man would far rather watch someone else fly and read of the narrow escapes from death when some pilot has had a forced landing or a blowout, than to ride himself. Even in the postwar days of now obsolete equipment, nearly all of the serious accidents were caused by inexperienced pilots who where then allowed to fly or attempt to fly — without license or restrictions about anything they could coax into the air …

Charles Lindbergh

We, 1928.

I am glad to see that you are riding the airlines. I hope you either take up parachute jumping or stay out of single motored planes at night.

Charles Lindbergh

To Wiley Post, 17 May 1931. Quoted in the 1993 book Will Rogers: A Biography.

The readiness to blame a dead pilot for an accident is nauseating, but it has been the tendency ever since I can remember. What pilot has not been in positions where he was in danger and where perfect judgment would have advised against going? But when a man is caught in such a position he is judged only by his error and seldom given credit for the times he has extricated himself from worse situations. Worst of all, blame is heaped upon him by other pilots, all of whom have been in parallel situations themselves, but without being caught in them.

If one took no chances, one would not fly at all. Safety lies in the judgment of the chances one takes. That judgment, in turn, must rest upon one’s outlook on life. Any coward can sit in his home and criticize a pilot for flying into a mountain in fog. But I would rather, by far, die on a mountainside than in bed. Why should we look for his errors when a brave man dies? Unless we can learn from his experience, there is no need to look for weakness. Rather, we should admire the courage and spirit in his life. What kind of man would live where there is no daring? And is life so dear that we should blame men for dying in adventure? Is there a better way to die?

Charles Lindbergh

Journal entry, 26 August 1938. Later published in The Wartime Journals, 1970.

It is about a period in aviation which is now gone, but which was probably more interesting than any the future will bring. As time passes, the perfection of machinery tends to insulate man from contact with the elements in which he lives. The 'stratosphere' planes of the future will cross the ocean without any sense of the water below. Like a train tunneling through a mountain, they will be aloof from both the problems and the beauty of the earth's surface. Only the vibration from the engines will impress the senses of the traveller with his movement through the air. Wind and heat and Moonlight take-offs will be of no concern to the transatlantic passenger. His only contact with these elements will lie in accounts such as this.

Charles Lindbergh

Foreword to his wife’s 1938 book Listen! The Wind.

How long can men thrive between walls of brick, walking on asphalt pavements, breathing the fumes of coal and of oil, growing, working, dying, with hardly a thought of wind, and sky, and fields of grain, seeing only machine-made beauty, the mineral-like quality of life?

Charles Lindbergh

Reader’s Digest, November 1939.

Sometimes, flying feels too godlike to be attained by man. Sometimes, the world from above seems too beautiful, too wonderful, too distant for human eyes to see.

Charles Lindbergh

The Spirit of St. Louis, 1953.

By day, or on a cloudless night, a pilot may drink the wine of the gods, but it has an earthly taste; he's a god of the earth, like one of the Grecian deities who lives on worldly mountains and descended for intercourse with men. But at night, over a stratus layer, all sense of the planet may disappear. You know that down below, beneath that heavenly blanket is the earth, factual and hard. But it's an intellectual knowledge; it's a knowledge tucked away in the mind; not a feeling that penetrates the body. And if at times you renounce experience and mind's heavy logic, it seems that the world has rushed along on its orbit, leaving you alone flying above a forgotten cloud bank, somewhere in the solitude of interstellar space.

Charles Lindbergh

The Spirit of St. Louis, 1953.

Science, freedom, beauty, adventure: what more could you ask of life? Aviation combined all the elements I loved. There was science in each curve of an airfoil, in each angle between strut and wire, in the gap of a spark plug or the color of the exhaust flame. There was freedom in the unlimited horizon, on the open fields where one landed. A pilot was surrounded by beauty of earth and sky. He brushed treetops with the birds, leapt valleys and rivers, explored the cloud canyons he had gazed at as a child. Adventure lay in each puff of wind.

I began to feel that I lived on a higher plane than the skeptics of the ground; one that was richer because of its very association with the element of danger they dreaded, because it was freer of the earth to which they were bound. In flying, I tasted a wine of the gods of which they could know nothing. Who valued life more highly, the aviators who spent it on the art they loved, or these misers who doled it out like pennies through their antlike days? I decided that if I could fly for ten years before I was killed in a crash, it would be a worthwhile trade for an ordinary life time.

Charles Lindbergh

The Spirit of St. Louis, 1953.

I may be flying a complicated airplane, rushing through space, but in this cabin I’m surrounded by simplicity and thoughts set free of time. How detached the intimate things around me seem from the great world down below. How strange is this combination of proximity and separation. That ground — seconds away — thousands of miles away. This air, stirring mildly around me. That air, rushing by with the speed of a tornado, an inch beyond. These minute details in my cockpit. The grandeur of the world outside. The nearness of death. The longness of life.

Charles Lindbergh

The Spirit of St. Louis, 1953.

Flying has torn apart the relationship of space and time; it uses our old clock but with new yardsticks.

Charles Lindbergh

The Spirit of St. Louis, 1953.

Didn’t see what you were looking for? Start again at the home page, or try another search: