GREAT AVIATION QUOTES

Scientific American

I hope you find what you are looking for. And maybe discover something you had no idea about!

There are 12 quotes matching Scientific American in the collection:

There is a lot of obscurity surrounding these questions. Indeed, I must confess that I have never encountered a simple answer to them even in the specialist literature.

Albert Einstein

On the aerodynamic question of how a wing works. Elementary Theory of Water Waves and of Flight, published in the journal Die Naturwissenschaften, 1916. In 1917, on the basis of his theory, he designed an airfoil that was built by Luftverkehrsgesellschaft in Berlin. It was not a success. In 1954 he described his excursion into aeronautics as a “youthful folly” (quoted in Scientific American, February 2020).

Everything that can be invented has been invented.

Falsely attributed to some version of the Commissioner of the U.S. Patent Office

Nope! Many researchers have looked for a real source for this line, as it appears in loads of quote books, often with different dates. None have found anything substantive. An excellent deep dive was done by the Quote Investigator who found lots of versions, like this one from the October 1915 Scientific American” magazine:

“Someone poring over the old files in the United States Patent Office at Washington the other day found a letter written in 1833 that illustrates the limitations of the human imagination.

It was from an old employee of the Patent Office, offering his resignation to the head of the department. His reason was that as everything inventable had been invented the Patent Office would soon be discontinued and there would be no further need of his services or the services of any of his fellow clerks. He, therefore, decided to leave before the blow fell.”

No such letter has ever been found. And while many people doubted the arrival of flying machines, there is no evidance of the Patent Office making this prediction.

When I meet God, I’m going to ask him two questions: why relativity? And why turbulence? I really believe he’ll have an answer for the first.

Attributed to Werner Heisenberg

The line is sometimes quoted, and sometimes said to be probably allegorical, and sometimes the great physicist is alleged to have said it on his deathbed! It's been seen in journals like Nature, Scientific American, and in several textbooks. But nowhere is a real solid citation found.

A similar witticism has been attributed to Horace Lamb in a 1932 speech to the British Association for the Advancement of Science:

“I am an old man now, and when I die and go to heaven there are two matters on which I hope for enlightenment. One is quantum electrodynamics, and the other is the turbulent motion of fluids. And about the former I am rather more optimistic.”

Of all inventions of which it is possible to conceive in the future, there is none which so captivates the imagination as that of a flying machine. The power of rising up into the air and rushing in any direction desired at the rate of a mile or more in a minute is a power for which mankind would be willing to pay very liberally. What a luxurious mode of locomotion! To sweep along smoothly, gracefully, and swiftly over the treetops, changing course at pleasure, and alighting at will. How perfectly it would eclipse all other means of travel by land and sea! This magnificent problem, so alluring to the imagination and of the highest practical convenience and value, has been left heretofore to the dreams of a few visionaries and the feeble efforts of a few clumsy inventors. We, ourselves, have thought that, in the present state of human knowledge, it contained no promise of success. But, considering the greatness of the prize and the trifling character of the endeavors which have been put forth to obtain it, would it not indeed be well, as our correspondents suggest, to make a new and combined effort to realize it, under all the light and power of modern science and mechanism? …

The simplest, however, of all conceivable flying machines would be a cylinder blowing out gas in the rear and driving itself along on the principle of the rocket …

We might add several other hints to inventors who desire to enter on this enticing field, but we will conclude with only one more. The newly discovered metal aluminum, from its extraordinary combination of lightness and strength, is the proper material for flying machines.

Flying Machines in the Future

Scientific American, 8 September, 1860.

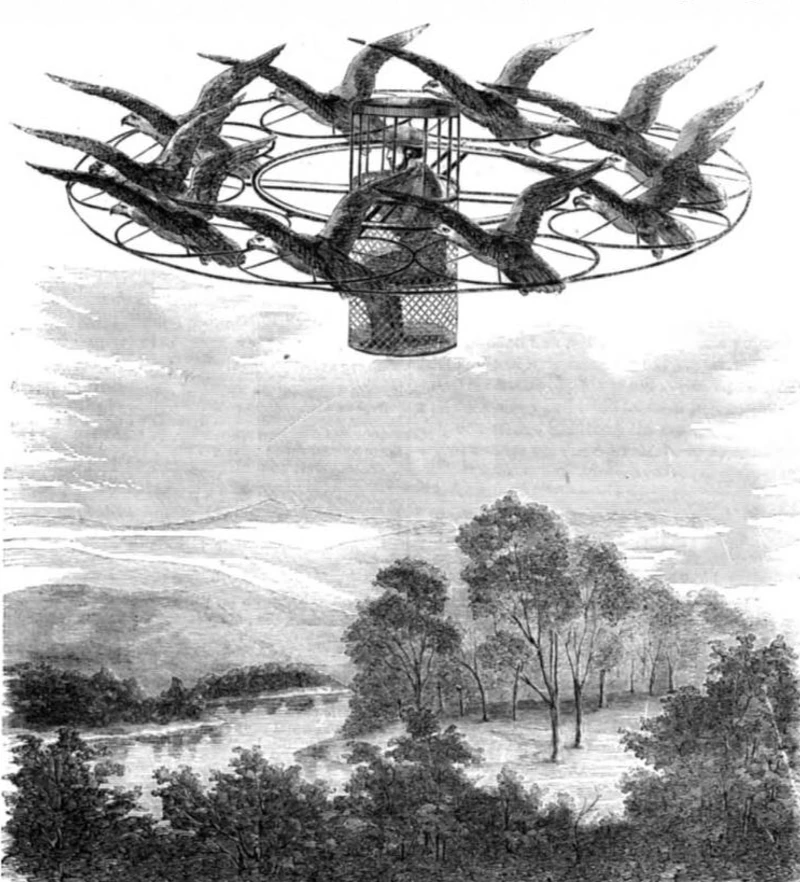

I venture to submit for publication a plan, to me apparently simple and feasible, that occurred to me many years ago, but that I have never found opportunity to put to the test of experiment. It is to do what man has already done upon the earth — make use of the powers of the inferior animals given to him to be his servants to effect his purposes. There are many birds noted for strength of wing and endurance in flight. The brown eagle and the American swan particularly suggest themselves. I propose to obtain a number of such birds (swans would probably be the most easily entrapped, but it might be a question whether they would bear our summer heats); ascertain by experiment their power of raising and sustaining additional weight to that of their own bodies, and attach them by jackets fitted around their bodies and cords to a frame work, which shall sustain a basket large enough to hold a man standing or sitting.

anon, from Baltimore

A Natural Flying Machine, Scientific American, 23 September 1865.

Considered as a sport, flying possesses attractions which will appeal to many persons with a force beyond that exercised by any of the similar sports, such as boating, cycling, or automobiling. There is a sense of exhilaration in flying through the free air, an intensity of enjoyment, which possibly may be due to the satisfaction of an inborn longing transmitted to us from the days when our early ancestors gazed wonderingly at the free flight of birds and contrasted it with their own slow and toilsome progress through the unbroken wilderness …

Once above the tree tops, the narrow roads no longer arbitrarily fix the course. The earth is spread out before the eye with a richness of color and beauty of pattern never imagined by those who have gazed at the landscape edgewise only. The view of the ordinary traveler is as inadequate as that of an ant crawling over a magnificent rug. The rich brown of freshly-turn earth, the lighter shades of dry ground, the still lighter browns and yellows of ripening crops, the almost innumerable shades of green produced by grasses and forests, together present a sight whose beauty has been confined to balloonists alone in the past. With the coming of the flyer, the pleasures of ballooning are joined with those of automobiling to form a supreme combination.

The sport will not be without some element of danger, but with a good machine this danger need not be excessive. It will be safer than automobile racing, and not much more dangerous than football. The motor flyers will always be somewhat expensive, as the best of materials and workmanship will be required in their construction, but there is a possibility that men will eventually learn to fly without motors, after the manner of soaring birds, which sail for hours on motionless wings. In such case the flyer would be so small and simple that the original cost would be very moderate, and the fuel expense done away with entirely. Then flying will become an every-day sport for thousands.

Wilbur Wright. Flying as a Sport — It’s Possibilities

Scientific American, 29 February 1908.

To affirm that the aeroplane is going to “revolutionize” the naval warfare of the future is to be guilty of the wildest exaggeration.

Scientific American magazine

The Myth of the Aeroplane Bomb, following Glenn Curtiss successfully dropping imitation bombs on a simulated battleship, 16 July 1910.

In part a flying machine and in part a deeath trap, the aeroplane has done both more and less that its sudden arrival among the great inventions of the age had promised. This combination of Chinese kite, an automobile motor, a resaurent fan, ballon rudders, junior bicycle wheels and ski runners, the whole strung together with piano wire and safeguarded with adhesive tape and mammoth rubber bands, sprang from toyland into the world of industry and finance with two plodding and pratical tinkers of genius — self-made engineers from the American school of try, try and try again — proved they could balance and steer it by a twist of its muslin. Now, the world turns a searching glance upon this machine which does so much and fails for treacherously.

Scientific American

May 1911.

The aeroplane … is not capable of unlimited magnification. It is not likely that it will ever carry more than five or seven passengers. High speed monoplanes will carry even less… Over cities, the aerial sentry or policeman will be found. A thousand aeroplanes flying to the opera must be kept in line and each allowed to alight upon the roof of the auditorium, in its proper turn.

Waldemar Kaempfert

Managing editor of Scientific American and author of The New Art of Flying, here writing in Aircraft and the Future, 28 June 1913.

The Director of Military Aeronautics of France has decided to discontinue henceforth the purchase of monoplanes, their place to be filled entirely by fast tractor bi-planes … This decision, which practically spells the death knell of the monoplane as a military instrument has not come altogether unexpectedly.

Ladislas d’Orey

How the War Has Modified the Aeroplane, Scientific American, 4 September 1915.

A joke told repeatedly at aviation industry conferences puts a man and a dog in an airplane. The dog is there to bite the pilot if the man so much as tries to touch the controls; the pilot’s one remaining job is to feed the dog. Many aviation veterans have heard the joke so many times that is possible to tell those in the audience new to the industry by their laughter.

Gary Stix

Scientific American magazine, July 1991.

Taking on the impossible is not necessarily easier, but it's more satisfying, it’s more motivating and, in the end, it’s more important.

Todd Reichert

Who along with Cameron Robertson and the AeroVelo team did the ‘impossible’, and built a human-powered helicopter that flew 10 feet into the air and hover in one place for 60 seconds, 13 June 2013. They won the American Helicopter Society’s Igor I. Sikorsky Human-Powered Helicopter Prize, along with $250,000. Quoted in Scientific American, November 2014.

In Wired magazine he also said: “It isn’t really about the prize. It’s about satisfaction of finishing something that you have set yourself to.”

Didn’t see what you were looking for? Start again at the home page, or try another search: